Graduate Student Paper

Sustainable Food Systems and Food Security

Fostering an Environmentally Sustainable Food System at KPU

Jordyn Carss, Tracey Kraemer, Tyler Thorpe, and Emily Townsend

SFSS 6110 - Environment and Food Systems (Instructor: Michael Bomford)

December 2021

Introduction

British Columbia's current local food system paradigm is unsustainable and vulnerable to changes in climate. This has come to light more than ever in the most current weather events that have disrupted our supply chains for both producers and consumers this year. We spend more than $8 billion on food annually in British Columbia, yet very little remains within the local economy in this bioregion (Mullinix et al., 2016). This budget could arguably be re-distributed to create more regionally-appropriate farming for place-based food production and consumption patterns that stay within planetary boundaries (Bomford, 2021). The question then becomes: how do we go about making our food system more sustainable in British Columbia, and more specifically within the Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU) community?

Like all systems, food systems are characterized by their interconnections, behaviour patterns, and outcomes (Meadows, 2008). Because food systems include everything from the production to the distribution of food, they are extraordinarily complicated systems that involve an ever-shifting network of interrelated entities, institutions, places and people that are all simultaneously influenced by change and drivers of it (Parsons et al., 2019). As such, before we can alter our system, we need to understand the relationship between its structure and behaviour (Meadows, 2008). For our food system, that means not only identifying every element that influences how our food is brought from farm to fork, but also how those elements interact and modify the world around them. In this paper, we intend to focus on how KPU's student association, food services, and farms can work towards a collective sustainable food system for its community.

Background

Food systems comprise economic, political, environmental, health and societal features that are interconnected but often have contrasting goals (Parsons et al., 2019). Due to this internal conflict, food systems are often a target of policy and planning to manage the side effects of the system on everything from community health to climate change (Hansen et al., 2020) and to buffer the effect of external forces that are beyond human control. The events of 2021, including a global pandemic and unprecedented rainfall and flooding, have exposed the weakness in British Columbia's food system, especially in the Lower Mainland. As revealed by these events, it becomes hard to focus on food sustainability during times of crises when food security is at risk.

In British Columbia, the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather events have severely impacted supply chains and peoples’ sense of food security. Both producers and consumers have felt the squeeze due to interrupted shipping lines, crop and livestock loss, and destroyed farms and production facilities. We are in a time when food insecurity is spotlighted, even to those for whom it was not a prior concern. Because of these events, people are gaining a sense of the fragility of the current food system structure, and are looking for ways to improve its resilience in the face of contemporary challenges.

In these uncertain times, community support through a regionally appropriate food system is paramount. Among its many benefits, regionally efficient food systems strengthen the vitality and resiliency of local economies, foster community participation, encourage health-conscious eating habits, and support cultural values attached to food, lifestyle, and cuisine. In the face of climate change and a growing sense of awareness of the impact of industrial food production on the environment, consumers are becoming more informed of the environmental problems associated with the food system and have a growing appetite for products that are sustainably produced. This has led to a growing number of "green consumers" who recognize that focusing their purchasing power on ethical and sustainable choices is an effective way to stave off environmental degradation, promote animal welfare, and eat healthier food (Darby et al., 2006; Satimanon & Weatherspoon, 2010). As such, there is a growing willingness to pay for locally-sourced, cruelty-free, and organic products, even when they cost more than conventional.

Movements that incorporate local and interdisciplinary approaches to the ways we produce and consume food are essential for our society to transition towards a more sustainable food system. However, having the right mindset is not enough to change the whole system. In addition, there must be appropriate land capacity, producers willing to shift away from industrial farming techniques, and sufficient government funding to ease the transition. The southwest bioregion of British Columbia is one such place that is capable of making the change. Evidence of this movement is already visible in the number of new food-based partnerships between local government, institutions and communities, providing us with more opportunities to explore how policy, science and practice can convene to generate robust change and support the transition to sustainability (IPES Food, 2015).

While it is encouraging that widespread momentum is building, province-wide participation is not required to incite meaningful change in our food system. According to the United Nations, "the food system includes the related resources, the inputs, production, transport, processing and manufacturing industries, retailing, and consumption of food as well as its impacts on environment, health, and society" (von Braun et al., 2021). As such, any entity that grows, sources and distributes food has a food system. KPU, in southwestern British Columbia, is one such entity with its own food system. From food production on campus farms to food service providers in campus dining halls, KPU has the ability to overhaul its existing food system and, with the right guidance, create a new food system that is local, sustainable, and secure with an overall smaller environmental footprint. Though it might seem like a small place to start, the inter-connectivity of food systems means that nothing happens in a vacuum, and decisions at a local level can have cascading effects that bring about sweeping change.

The intensification of our modern food system on a local and global scale is a primary driver in shifting our planetary boundaries, largely affecting biodiversity loss, land use change and climate change (Stockholm Resilience Centre, n.d.). In the context of British Columbia and specifically the KPU community, we will analyze how regionally appropriate farming can be an antidote to the centralized, intensified, global farming currently affecting our food systems.

Current context and challenges

KPU Student Association & Campus Food Service Facilities

KPU was established in 1981 as an institution with two campuses and a primarily vocational focus. It has evolved into an accredited university with five campuses (three in the City of Surrey, one in the City of Langley and one in the City of Richmond), offering a unique blend of academic, trades and horticultural training (KPU, 2021a). With more than 20,000 students enrolled annually, more than one-quarter (27% in 2019-2020) are international students and more than half (67% in 2019-2020) are bilingual, indicating high cultural diversity (KPU, 2021b).

KPU faces unique challenges in its efforts to develop a sustainable food system because it is a commuter school (i.e. no on-campus student housing) spread over several municipalities. Students are not living or working on or near campus, which means that they spend minimal time on site and have to dedicate time they might otherwise spend participating in campus-based programs and activities traveling between their homes, work, and school. As such, participation in events that aim to raise awareness about campus sustainability is generally low.

In addition, land prices surrounding the five campuses are some of the highest in Canada, making expansion for increased local food production difficult. Due to both students not living on campus and the high cost of land, students tend to lack a sense of place, a belonging to the land that comes from owning property or being able to contribute to the maintenance of a garden (E. Pedersen, pers. comm., October 18, 2021). Without a strong sense of place, students will struggle to feel any responsibility to sustainability initiatives because they do not feel ownership over the outcomes. This sense of apathy is exacerbated by the fact that most students only spend four years or less at KPU, making any long-term initiatives hard to establish when students know they will be gone before any real progress is made (E. Pedersen, pers. comm., October 18, 2021).

Despite these challenges, purposeful changes are happening at KPU to improve campus sustainability, and a primary focus is the campus food system. In 2021, Chartwells Canada was selected as the official food service partner for all KPU campuses. Their four key areas of emphasis are: locally-sourced ingredients, chef-inspired menus, technology-focused solutions, and upcoming space renovations (KPU, 2021c). “This partnership reflects the shared values and vision of [KPU and Chartwells Canada]; to enhance the student experience with a focus on sustainability, creativity, quality, and innovation." (KPU, 2021c). The first principle of their participation, locally-sourced ingredients, is secured through the Buy Local program.

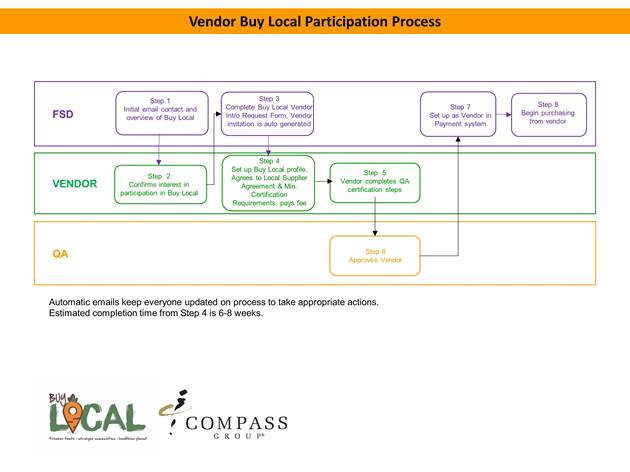

The Buy Local program adopted by Chartwells Canada at KPU promises to source a minimum of 30% of food and beverage products from local vendors, including KPU farms. The agreed scope for the term ‘local,’ according to Chartwells Canada, is that "the product must be grown or produced in the region, or province.” (S. Shamsuddin, pers. comm., November 2, 2021). As long as they can meet certification minimums and pass quality assurance audits, eligible producers include small and medium-sized, family-owned, owner-operated, and community-based farmers and producers. Producers must meet health and safety requirements, however, there are currently no requirements within the program that specifically address environmental issues, leaving room for significant policy improvement when it comes to the environmental sustainability of their suppliers.

While the Buy Local program at KPU is an ambitious step towards making the campus food system more sustainable, the program is currently not being actively marketed. There is very little evidence of its promotion both on-campus and online, so most consumers are not aware of the effort Chartwells Canada is putting in support for local food production. In addition, due to COVID-19, student presence on campus is at an all-time low. Therefore, food service outlets are experiencing extremely low sales, which has limited Chartwells Canada's ability to increase the amount of locally-sourced products on offer. When the subject was broached with Chartwells Canada, the response holds both promise and frustration: “contractually we are only obligated to source 30% (local product) but once we start seeing more sales at KPU, that target could increase. Currently sales are very low and do not support the program" (S. Shamsuddin, pers. comm., November 2, 2021).

Buy Local is a social movement that serves to re-regionalize food supply and reduce dependence on imported products. It encourages consumers to support independent producers rooted in their home communities (McCaffrey & Kurland, 2015). It also serves to reduce dependence on the vertically-integrated corporate productionist food regime which dominates our food system today. Buy Local is a crucial component to fighting supply chain issues that threaten food security in our communities and is an important first step in the formation of a regionally appropriate food system. Food service contracts and use of on-campus marketing could bolster KPU’s commitment to sustainability and support the communities in which it operates.

KPU Farms

In addition to forming partnerships with service providers that value locally appropriate sourcing, KPU has an advantage over most institutions in terms of its capacity to become more sustainable because it has the ability to produce its own food. KPU maintains a teaching and research farm in the City of Richmond, BC. Located at the Richmond Garden City Lands, a 55-hectare site within the Agricultural Land Reserve on the east edge of Richmond, the KPU farm grows various types of produce using moveable ‘High Tunnels’ (KPU, n.d.), and a passively-heated, domed greenhouse. Currently, organic produce grown on the farm is sold at the Kwantlen Street Farmer’s Market, and through KPU’s campus cafeterias. The farm also donates food to the Richmond Food Bank.

While the KPU Farm benefits from its proximity to the Richmond campus and to populated areas as it is easily accessible to students and is close to the farmers market, there are some disadvantages to its location. A key limitation of the KPU farm is that it is constrained in its ability to expand and produce more food, due to both the high price of land in Richmond and characteristics of the peat on site. In the early 20th century, the Richmond Garden City Lands hosted a rifle range. This, among other historical industrial activities, have resulted in the peat being contaminated with heavy metals (City of Richmond, 2014). To make the site suitable for farming, eight acres of the contaminated peat was covered with 70 cm of mineral soil, which was then topped with 10 cm of compost, onto which cover crops were grown. As such, expansion of the cultivated area at the Richmond Garden City Lands site would require further amending of soil, which requires extensive planning and coordination.

Another factor to consider is that Lulu Island, the largest island in the municipality of Richmond, is largely comprised of former peatland bog wetland, which has primarily been developed or converted into cropland (Bomford, 2021). Peatland is a particularly important type of ecosystem because it stores about a third of all terrestrial carbon and it has the ability to sequester carbon indefinitely (Bomford, 2021). This is an important challenge to consider when it comes to our efforts to remain within the planetary boundaries of land-system change and climate change. Although most of the peatland bog wetland around Lulu Island has been converted, there still remains a few areas of this region with untouched peatland. The challenge then becomes protecting this important ecosystem in the face of development and agricultural land use change.

The conservation of a large ecological space often means that there is a trade-off with furthering infrastructural development and agricultural land conversion. For example, the Richmond Garden City Lands, which lie on peatland bog, has focused on both restoring the wetlands and demonstrating sustainable farming systems (City of Richmond, n.d.). In the face of a growing and hungry population, preservation of pristine ecological systems poses challenges. Nevertheless, KPU and the City of Richmond are collaborating to chart a sustainable path to a better future. The Richmond Garden City Lands project combines science-based recommendations from KPU with feedback garnered from local government to create a sustainable food system for students and the community (City of Richmond, n.d.).

An example of this collaboration can be seen through the soil transfer project between KPU, private industry, and the City of Richmond. Expansion at the Vancouver International Airport (YVR) required excavation of mineral soil from the site. This soil was transferred to the Garden City Lands, where it was placed on top of the peat (KPU, 2019). By leaving the peat undrained and intact beneath the drained and cultivated mineral soil, the KPU farm retains long-sequestered carbon in the peat, while sequestering additional carbon in the mineral soil above. This partnership benefited both the KPU farm, which needed the soil for farming, and YVR, which was able to save money on soil disposal and trucking fees. In addition, the conservation of the peat as a natural carbon sink is a benefit shared by all parties (M. Bomford, pers. comm., October 1, 2021).

Finally, KPU is primarily an educational institution, offering a unique opportunity for students to investigate and support local food systems through applied research in agriculture (Mullinix et al., 2016). The university currently is one of few universities to offer both theoretical and practical knowledge on sustainable agriculture. KPU is showing students how to grow food and understand our food system, through programs such as their Bachelor of Applied Science in Sustainable Agriculture, Graduate Certificate in Sustainable Food Systems and Security, as well as the Farm Schools and Incubator Program. Through education, partnership, and innovation, KPU and the City of Richmond are working to reform local the local food system to make it more sustainable, more secure, and more compliant with our planetary boundaries (City or Richmond, 2020).

Recommendations

In addition to its use as a synonym for establishment or school, it is no coincidence that the word institution has a meaning that implies resistance to change. Universities, in particular, frequently embody both definitions of the word. Fortunately, our post-secondary institutions are becoming less rigid in their doctrines, and more amenable to the demands of an increasingly socially and environmentally conscious generation. While it is far from easy, inciting campus-level change is at least now possible, and when navigated through the appropriate channels, can be achieved.

Kwantlen Student Association

The following recommendations are derived from research and conversations with members of the Kwantlen Student Association on how to bring about meaningful campus-level change with the goal of creating a sustainable campus food system:

- Implement the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into long-term campus planning and policy development and ensure that there is adequate data collection in place so that leading and lagging indicators can be monitored. Because the SDGs are well established and well researched, they are easier to implement than brand new policies.

- Start with small changes that are possible to accomplish in a short period of time. Because students only spend 4 years or less on campus, short-term goals are more likely to be supported. A series of small changes can be enough to cause large, systemic shifts over time.

- Update the KPU 2050 Campus Plan to include a vision for the KPU food system. Food access and security is mentioned only once and there are no targets for the sustainability of the food system.

KPU Campus Food Service Facilities

The following recommendations are derived from research and conversations with staff from Chartwells Canada on how campus food service facilities can support a shift towards a more regionally appropriate, local food system:

- Implement reporting timelines and report requirements in food service contracts. Increase transparency by making these contracts visible and form a committee that is responsible for ensuring these contracts are being followed and that the reports are being reviewed upon application for contract renewal. Students should make allies in the administration who are tasked with holding the providers accountable.

- Expand the contracts between campus food services and their local suppliers to include environmental responsibility requirements, including commitments to minimum environmental standards (e.g., organic, bio-dynamic, natural pest management) so that KPU's commitment to sustainability is better served

- Set conditions that compel producers to prove their commitment to lowering their emissions, reducing their carbon-footprint and supporting local environmental initiatives and organizations. There are a variety of approaches for vendors to take to tackle these goals in a reasonable manner for their business. Resources and recommendations should be provided by the overseeing KPU committee.

- As, under the current contract with Chartwells, suppliers are responsible for delivering their products to KPU (S. Shamsuddin, pers. comm., November 2, 2021), encourage the use of zero or low emission vehicles, or work with the farmers to coordinate schedules and work together to reduce the number of trips to and from campus.

- Consider upgrades to facility operations including the use of alternative energy sources, waste reduction technologies, and improving linkages between inputs and outputs for production system self-suppliance.

- Expand ingredient procurement to include alternative proteins, organic products, pesticide-free products, and plant-based products.

- Support local environmental initiatives by partnering with schools, community organizations, community gardens, charitable organizations.

(S. Shamsuddin, pers. comm., November 2, 2021)

- Increase awareness of the Buy Local program and highlight its benefits through improved marketing to increase sales at food service outlets on campus.

- Develop a KPU awareness campaign that celebrates local producers, KPU farms and farmers, and community engagement.

- Create a relationship between zero-waste, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and ecosystem health and the food system, which were ranked by KPU students as three of their top five sustainability priorities (KPU, 2020d). Help students make the connection that their food purchasing choices at KPU can support their sustainability goals.

- Use tools such as print and digital media visuals with QR codes to increase awareness of vendor sustainability goals, Buy Local resources, and food system and health information to help students make more informed decisions about which food service outlets to support.

KPU Farms

KPU's farms, specifically the Richmond Garden City Lands, presents an opportunity for the KPU Richmond campus to have a greater impact on KPU’s food system, through education, community collaboration, and ecological preservation of a vital ecosystem. The university currently has a large portfolio for theoretical and practical sustainable agriculture programs that provide an opportunity for students of different backgrounds and ambitions to get involved with food systems and for KPU to train its community to be more sustainable producers and consumers.

The following recommendations are derived from research and conversations with KPU farm staff on how campus food production can play a larger role in the community's food system:

- Process more of the farm's products on campus, creating more value-added items, and offering additional learning opportunities for the student farmers.

- Raise livestock on the KPU farm for an integrated and regionally appropriate approach to farming.

- Use hyperaccumulator crops (e.g., sunflowers) to mitigate soil contamination issues in the Richmond Garden City Lands. Hyperaccumulator crops are known to extract heavy metals from the soil (Chauhan et al. 2020) and can still be processed by students to create a marketable product.

KPU and the Community

The initiatives between KPU and other community entities illustrate how a university can further sustainable agricultural and ecological preservation practices by working in collaboration with local governments and institutions. This can be seen in the partnership between KPU and the City of Richmond when they worked together in the development of the Richmond Garden City Lands.

The following recommendations are derived from research and conversations with KPU staff on how the university can play a larger role in the local food system through additional collaboration with entities in the community:

- Hold regular community forums initiated by KPU's student body, including Richmond community members and local governments to determine upcoming projects related to food systems.

- Seek opportunities for local government and institutional funding to support students involved in sustainable agriculture research.

- Use the tools already in place at KPU to include other members of society in moving forward the movement of sustainable food systems, for both the Richmond and KPU community.

With the above recommendations, the joint efforts between KPU's student body community, food service providers, production capacity, and collaboration with local governments, the university can be a leader in promoting ecological preservation and sustainable agricultural practices.

References

- Bomford, M. (2021). Land Use Change in Richmond [PowerPoint slides]. Kwantlen Polytechnic University SFSS 6110: Environment and Food Systems.

- Bomford, M. (2021). What can BC's floods teach us about our food system? [PowerPoint slides]. Kwantlen Polytechnic University SFSS 6110: Environment and Food Systems.

- City of Richmond. (n.d.). Garden City Lands.

- City of Richmond. (2014). Garden City Lands Legacy Landscape Plan.

- City of Richmond. (2021). Sustainability Progress Report 2015-2020.

- Darby, K., Batte, M.T., Ernst, S., & Roe, B. (2006 July 23-26). Willingness to pay for locally-produced foods: a customer intercept study of direct market and grocery store shoppers. American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Long Beach, California.

- FarmFolk CityFolk. (2021). BC Seed Security Program.

- Hansen, E., Robert, N. & Tatebe, K. (2020). Planning to eat; A new decade for food planning. Plan Canada 60(1): 19-23.

- International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES Food). (2015). The new science of sustainable food systems; Overcoming barriers to food system reform.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (n.d.). Graduate Certificate in Sustainable Food Systems.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (n.d.). Incubator Program.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2018). Vision 2023, Draft 2.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2019). Department of Sustainable Food Agriculture & Systems - Annual Report.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2021a). KPU 2050 Official Campus Plan.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2021b). Student Profile: All KPU.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2021c). Campus Food Services.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). (2021d). KPU 2050 Sustainability Plan.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University. (n.d.). KPU Farm Schools.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University. (n.d.). Sliding High Tunnels.

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University. (n.d.). Sustainable Agriculture and Food.

- McCaffrey, S.J. & Kurland, Nancy B. (2015, June 26). Does “Local” Mean Ethical? The U.S. “Buy Local” Movement and CSR in SMEs. Organization & Environment 28(3), 286-306.

- Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in systems; A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Mullinix, K., Dorward, C., Sussmann, C., Polasub, W., Smukler, S., Chiu, C., Rallings, A., Feeney, C., & Kissinger M. (2016). The Future of our Food System. Institute for Sustainable Food System: Summary of the Southwest BC Bioregion Food System Design Project.

- Parsons, K., Hawkes, C. & Wells, R. (2019). What is the food system? A food policy perspective. City, University of London: Centre for Food Policy.

- Richmond Food Security Society. (2021). Urban Bounty. Richmond Community Seed Library.

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. (n.d.) The nine planetary boundaries.

- von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L., Hassan, M. & Torero, M. (2021). Food Systems – Definition, Concept and Application for the UN Food Systems Summit. United Nations Food Systems Summit 2021 Scientific Group.